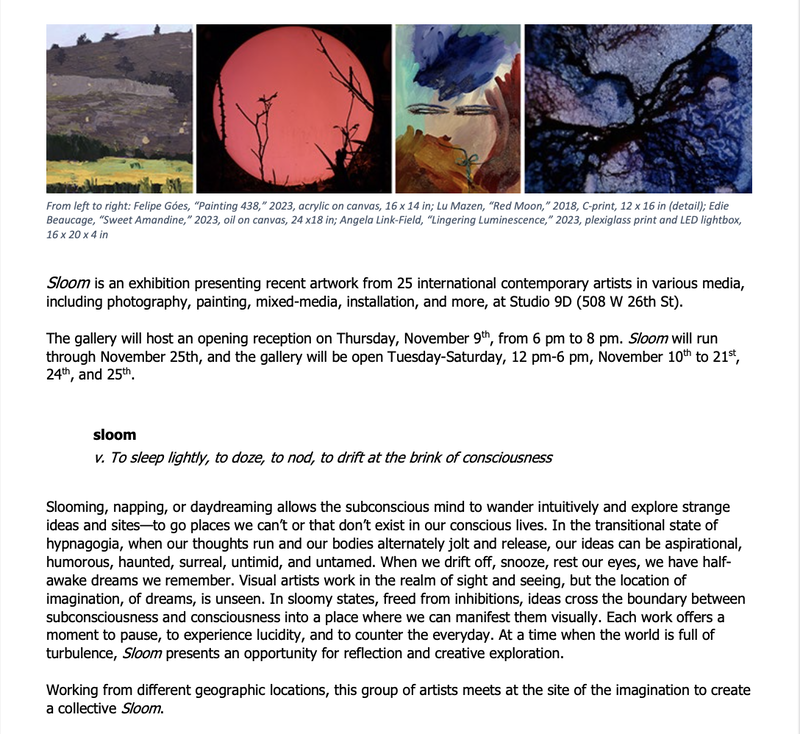

|

Sheela na gig, 2024, oil on canvas, 15.7 x 19.6 inches. A while back, as I sorted through my old medical records, I came across a couple of stills from the videoscope used during my uterus surgery (where they removed some fibroid tissue and endometriosis threads). And I found them beautiful, not in the sense of a frilly, nice loveliness, but in a deeper, poignant way, as corporeal mess, with its darkness and mystery. Beauty that points to what the body, every body, can endure, to its resilience. That's where the beauty lies. And the strength.

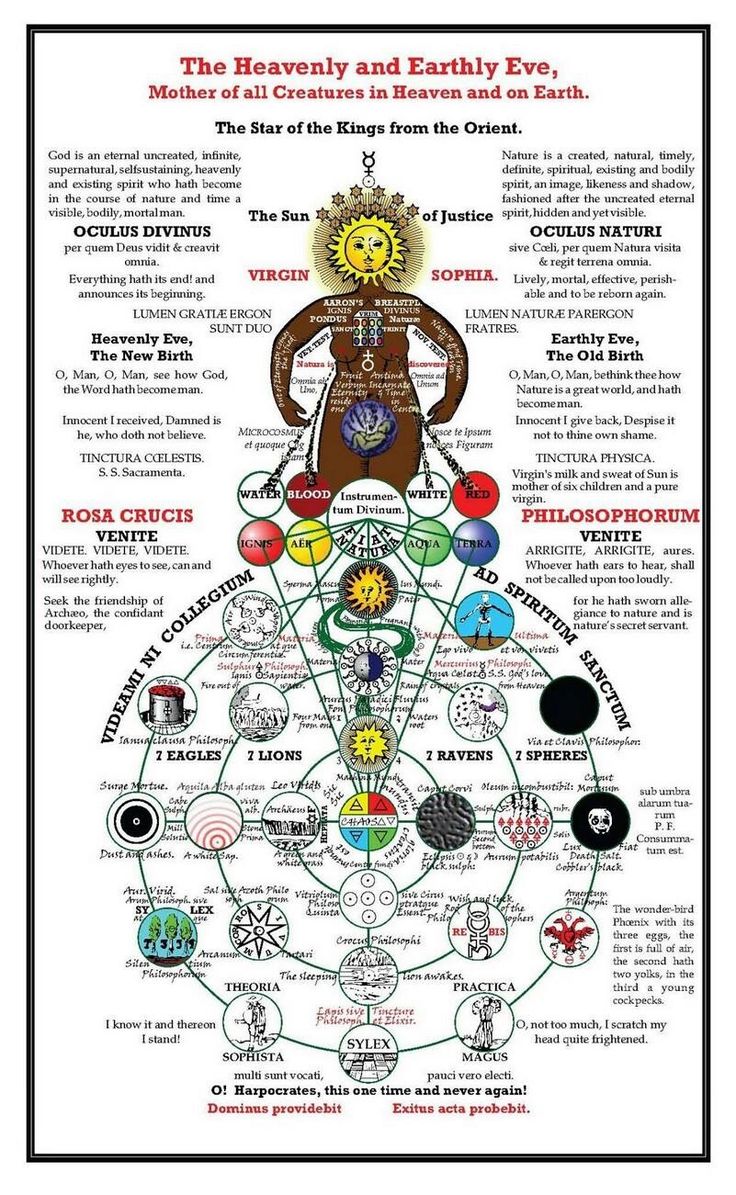

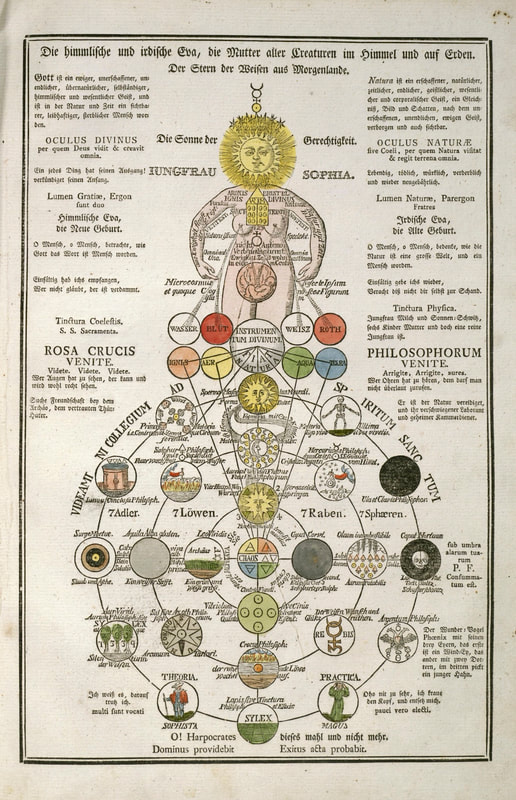

I used them as basis for a self portrait as a ‘sheela na gig’ figure, adding the scars my body carries from cancer surgeries (thyroid and breast). Painting, I felt immersed into the knowledge of my body around those lived experiences but also into a deeper reservoir of intuition, resilience and collective ancestral memory that flows through and around us all. Tara Brach - in her podcast episodes July 4 and July 10, 2024- talks about 'embodied presence'. She discusses how that quality of presence allows us to be truly available for the other, present for the other and more open to an emphatic, compassionate being in the world, as sharing a common humanity as fleshed human beings. This in opposition to living dissociated from our bodies, living in a virtual reality of thoughts and of 'othering', hostile divisoning the world suffers from these days. Last month I had a pre-op CT scan for a planned parathyroidectomy. Looking at those images also allow me to sink deeply into my body. I will no doubt paint based on those images as well. Something happened as I was doing research for the this work from the anatomy lesson I’m revising. I was looking for motifs to add in the background of this first painting, thinking of plants and lilies, birds maybe? So winged creatures. Angels perhaps? This led me to a book on angel iconography. I leafed through it to look at the illustrations and suddenly I felt a jolt of recognition. I saw an illustration from ‘Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucians from the 16th and 17th Centuries,’ in my work. Can you see it? The figure with her baby in her womb is The Heavenly and Earthly Eve, mother of all creatures in Heaven and on Earth. The Great Mother Goddess as she comes across to me. Of course there's a lot to be written about the figure, her origins, different interpretations in different traditions, merged into patriarchal christianity's Virgin Mary.

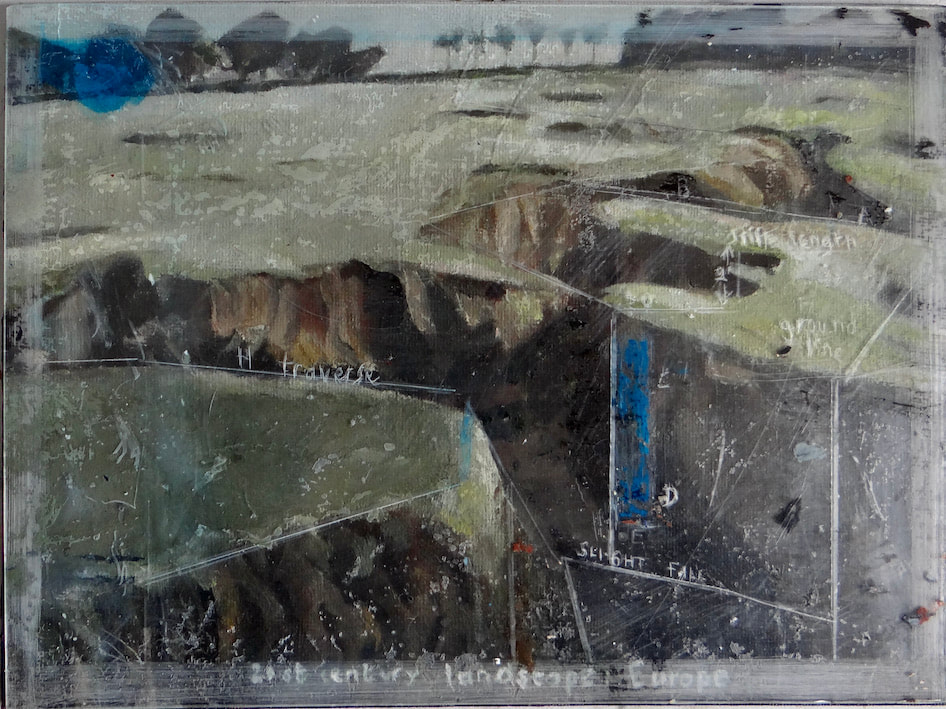

This is what slow painting means to me. It’s only through this kind of dialogue between the painting and the images that arise from the deepest layers of yourself, from deep inner work through the process of painting, that a meaningful work can ensue. Maybe it’s like an individuation process, a sort of spiritual discipline? And it doesn't end as I leave the studio. Obviously such a painting process can’t be hurried. It’s what I enjoy most about painting. I’m now thinking of incorporating symbols of this illustration into the tiling of the second work. More later? 21st century Landscape: Europe. Oil on canvas, with added acrylic sheet, in-carved with directions to dig a trench from military documents, 18 by 24 cm.

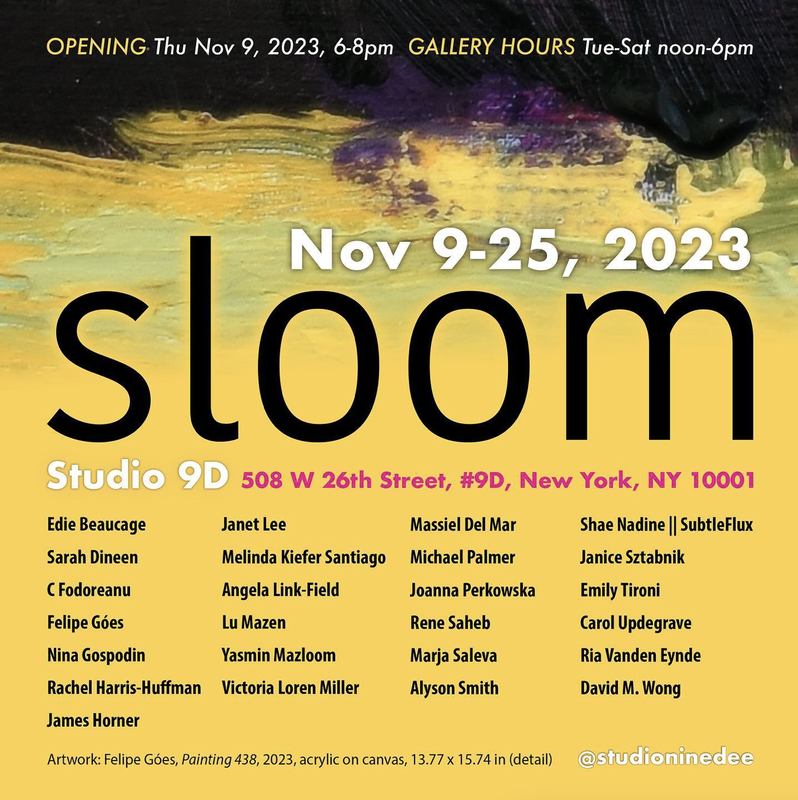

21st Century Landscape: Europe' can be viewed as a politicised landscape. It juxtaposes imagery of Europe's historical warfare trenches with the metaphorical divides that currently separate its societies, calling for a transcendent dialogue. It serves as a testament to the enduring human struggle for connection and peace. Painted on a small canvas, it exemplifies the notion that size does not dictate significance; viewers must draw near to discover the image's layered meaning. The work thus emphasises that sometimes the most profound messages are conveyed in the quietest of voices. ‘An eye for an eye and soon we'll all be blind,’ said Gandhi. ‘Nie wieder Krieg’ was Käthe Kollwitz’s cry on her 1924 lithograph. I read on the National Gallery of Art that it’s ‘not on view’… timely as it is. This landscape painting portrays an inner and outer landscape completely cut up by trenches as we all seem to be in a constant flaring up of conflicts. Imagine we would all live from a shared core of being a human being, vulnerable and resilient, valuing our interconnectedness and interdependence instead of the current ‘bad-othering’ that spins out of control into straight out war accompanied by the cynicism of world leaders warring over the bodies of their population they vowed to protect. We might be called naive, but seriously, I myself do not want to be co-creating a society in which we’re shouting (shooting) at one another across an unbridgeable divide (trench). I believe we all share a deep longing to trust the basic essence of being a fleshed human being, a certain quality of presence, a benevolence, a larger sense of self that recognises that we’re all just living life as best we can on this planet, and that we’re connected that way. Imagine we’d intentionally train ourselves to look for that quality and remind each other of it. Would that not be our human superpower to direct us towards a society with a social contract of care? My artwork '21st century landscape: Europe', is on view at studioninedee, 516 W 26 St, Chelsea, NY from 11/9>11/25 in a a group exhibition SLOOM featuring 25 international contemporary artists. Cassandra/Self Portrait of the Artist as a young Girloil on canvas, 62 by 78 cm, 2023 In 2021, I began making a series of studies of the works of Velázquez. As I begun this particular work, which I then titled 'The Infante,' I reused a 2018 painting on linen that depicted the Statue of Liberty. Probably significant that I painted her over the Statue of Liberty also, considering the constraints on the freedom of women to carve their own futures I'm addressing here. I decided to repurpose the canvas, drawing inspiration from not only Velázquez (the wide peplum dress in La Infanta Margarita, portraits of her were sent to Vienna to inform Leopold of what his young fiancée looked like) but also from Klimt (the stance of Mäda Primavesi) and Camille Claudel (sculpture La Petite Châtelaine). Throughout this process, I wanted to explore the theme of the socialization of girls, incorporating elements from these artists to convey my message. It became more personal along the way. The project evolved through several stages, with the first 'finished' stage featuring a girl, dressed in a yellow gown that reminded me of Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1892 novel, "The Yellow Wallpaper," an important early work of American feminist literature for its illustration of the attitudes towards mental and physical health of women in the 19th century. However, I felt that this image wasn't quite bold enough in what I wished to convey about my own youth's circumstances. I then decided to paint the background in red, which ultimately led to the final result. To me, the painting unintentionally grew to feel like a self-portrait, even though the head is that of La Petite Châtelaine, a sculpture by Camille Claudel, who found herself confined in an asylum by her brother and never sculpted again. Perhaps I identify with that aspect of her as an artist who had her creative growth stunted. As a child, I experienced an isolated upbringing and was denied the opportunity to attend art school due to restrictive parenting. I was not allowed to play with other children or have friends over to our house. Despite receiving praise during an art class from a nun who encouraged me to nurture my talent, I was expected to pursue more conventional subjects for a stable career, which led me to study mathematics. I never rebelled against these constraints, the thought never even entered my mind. In the final work, I can find echoes of this upbringing. While I'm painted with an open mouth -screaming, shouting, singing?- there is no sound coming out, I remain silent. My inner world has always been vibrant and filled with color, as I spent my time reading, drawing, and teaching myself to paint at home. This was my refuge, a totally solitary path of self-discovery. No wonder I am still extremely introverted, while I'm just as much extravert in my paintings. This work feels like such a good fit as book cover for Alice Miller's 'Drama of the Gifted Child' to me? I'd welcome such an offer~ Statement:

Silenced Whispers captures the impact of restrictive parenting on the artistic spirit, offering a visual reflection on the untapped potential and stifled creativity that result from unfulfilled artistic aspirations. This introspective portrait portrays a young girl who is trapped within the confines of societal expectations, her artistic voice silenced before it had a chance to bloom. The portrait hopefully can challenge viewers, to reevaluate the societal constructs that hinder the development of creative expression, which is detrimental for the culture in general. It may remind us of the importance of fostering an environment that nurtures and supports artistic growth. What does the title 'A Still Life' stand for? A still life, the series of still lifes is about a longing for stillness, for slowing down, a 'different' way of looking than the trance of scrolling through pervasive images, coming home to ourselves in the wide open space of our deepest layers. From where the beauty of the world gently reveals itself to us, the elegance of the fragile life that we all, each of us, weave together with the objects we touch, our dreams, memories, desires, hopes and relations. It even feels a bit rebellious to spend that much time quietly observing these objects, making time stand still while the world races on in chaos.

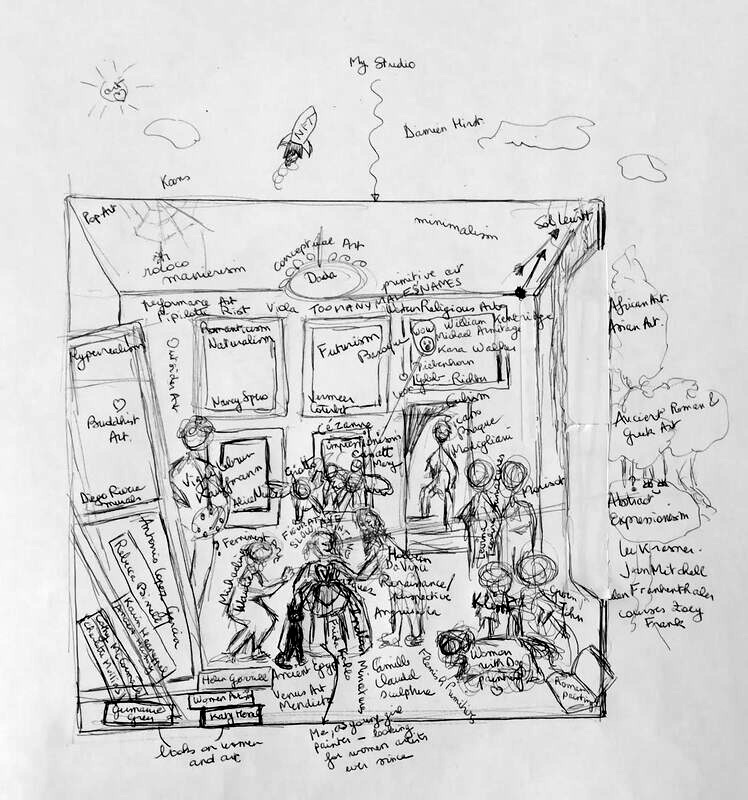

In her poem 'This Big Fake World," Ada Limón writes about it in this fragile way: The object is to not simply exist in this world of radio clock and moon pies, where holidays and lunch breaks bring the only relief from the machine that is our mind humming inside of its shell. Shouldn’t we make a fire out of everyday things, build something out of too many nails and not wonder if we are right to build without permission from the other dull furniture? Out of this small plot we are given, small plot of cement and electrified wires, small plot of razors and outlandish liquor names, let’s make a nest, each of us, of our own pieces of glass and weeds and names we have found. Somewhere along the banks of this liquid world let all of us hold close to the lost and the unclear, and, in our own odd little way, find some refuge here. These paintings are based on A Still Life, 4, The Kitchen Sink, a start of a series of iterations towards more and more abstraction a bit like images fade and distort in our memories. That's how my mind works anyway. All iterations are 30 by 30 cm, oil on canvas board. I worked on these first iterations during Zoey Frank's course, "Breaking the Space". Winter. I’m slowly exploring my natural eb and flow in art making. I get frustrated about the lacklustre light in my studio and feel totally unable to see what color I’m mixing. I do have a special daylight light system, but blah, it’s not at all the same as getting up in the morning with a clear sky and natural light present and waiting for me and my clean brushes. I find myself reading a lot, pondering on how to finish paintings I started during a Zoey Frank course, juggling new ideas in my mind, thinking about new painting approaches for me while looking and listening to other artists talking about theirs. For instance it can be a formal approach, a challenge to do a painting that answers a certain formal, maybe compositional question, like ‘can I make a painting where the viewer’s eye can freely travel around the surface of the painting?’ Or, ‘can I do a high chroma painting and how would I create space?’ And all the while always dialoging with art history. Or more conceptually, cerebral perhaps, paint about sociologically inspired stuff, the what versus how to make the painting. In winter I guess I’ll wait for my seeds to come up in spring and then I’ll say, like Matt Damon in The Marsman, when a potato shoot springs, he cups the tiny leafs in his hand and says ‘Hi there,’ to it. The challenge is how can I be patient and trust the process. I actually tend to use a lot of my own ‘sh*t’ too, metaphorically that is. Anyway. Last month I got some books from the second hand bookstore on art history, Taschen’s 'Women Artists in the 20th and 21st century', 2002, Whitney Chadwick’s 'Women, Art and Society', the 1990 ed. Thames and Hudson (I had an issue with it, but can’t remember where now), Germaine Greer’s 'The Obstacle Course, The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work', Farrar Straus Giroux, NY, 1979 and ordered a copy of ‘Mix and Stir, New Outlooks on Contemporary Art from global Perspectives', edited by Kitty Zijlmans and Helen Westgeest, Plural Series Valiz, Amsterdam, 2021. I started with Kitty Zijlmans’ book Kunstgeschiedenis (Art History) from the Elementaire Deeltjes series (Amsterdam University Press, 2018) I took out at the library. Insanely interesting it hints at alternatives to study art beyond national constraints and cultural dominances and hierarchies and how to braden the approach of art to its global dimensions, as opposed to the Eurocentric approach that ran galore in my schooling. And white, patriarchal and capitalist I might add. In her book, she refers to US art historian James Elkins who had the most wonderful course of short video’s on Youtube “Concepts and Problems in Visual Art.” *Look up his channel ‘James Elkins’. In lecture H2 How does Art History appear to you?, he invites his students to do an intuitive drawing of art history. Do a drawing of everything you think about in art, arranged in the way you feel about the topics or items you include. WOW?! What an eye opener! I wish I had a professor like that in my art classes. But I’m not complaining, I’ll do a drawing myself here and plant another seedling. I'll use my fave painter's fav painting: Velázquez' 'Las Meninas' and organise my stuff around it. Collage writing, that’s what this looks like, as my eye goes around and adds stuff in my sketch of art history, memories float up and then my mind jumps onto something else I want to add. Or is that just how the mind works, is that the way we tell the story of our life to ourselves? Mind you there are infinite variations on the elements I added. And maybe there’s no ONE painting that could come out of this. A puzzle technique. Weaving together. Now I’m thinking of Lidia Yuknavitch's book 'Thrust', I still didn’t finish and that addresses just that. Who am I? What do I stand for? What are my beliefs? WHY do I make art? What do I want to leave in the world, how would I want my work impact the world? *Ego-Inflation red flag? Naivety red flag?* What is my purpose?

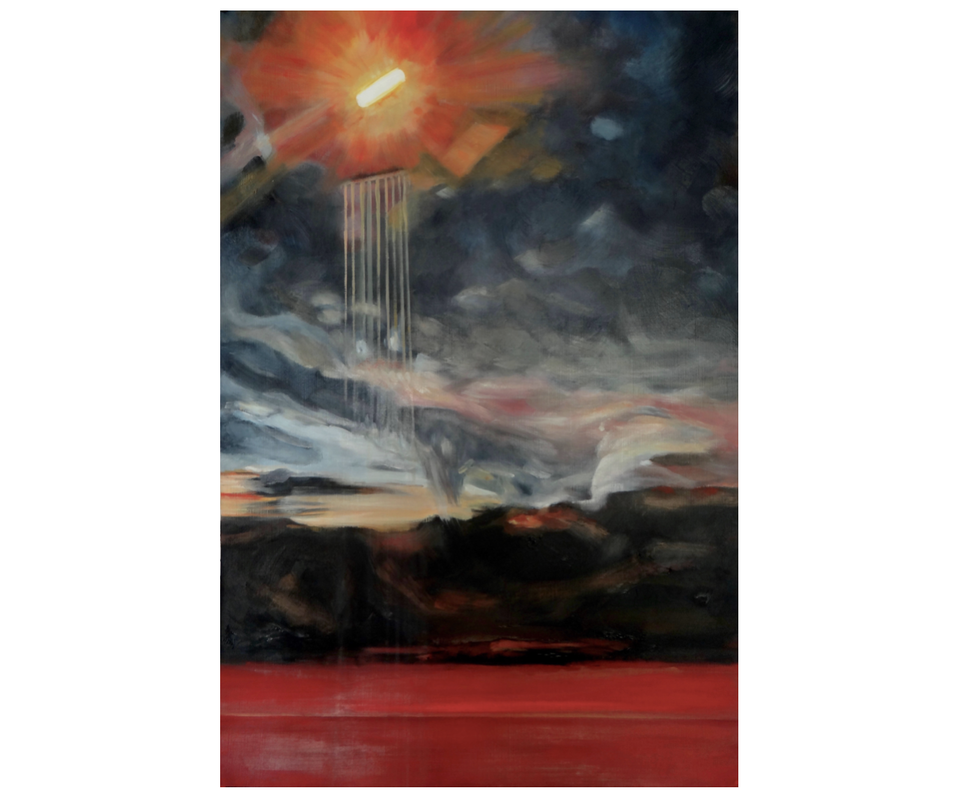

The artist statement seems to want me to know answers to all those questions and write it in a compact concise two paragraph text. All it does though is bring me into an existential cramp, trying to figure out the response to age old philosophical, spiritual, religious questions. I’m very aligned with a Buddhist take on that. Usually “I am” a little self, made up of wants, fears, successes and failures. That’s sort of limiting and scanty, almost a logical precursor of the commodification of my work. When asked this question about who we are, a teacher responded by holding up a really large sheet of white paper and he drew a small V-shape on it. Then he asked the students what it was a picture of and most responded that it was a flying bird. “No,” he said, “it’s a picture of the sky with a bird flying through it.” He showed that what you pay attention to about yourself, about life, determines your experience. Focusing on the bird is like paying attention to what’s most obvious in the foreground of your mind, thoughts, sensations, feelings. Shifting to seeing the sky is like opening to the context that’s holding those experiences, the ocean of awareness, an alert openness from which you perceive all that is happening. It seems to me to paint is holding that question “who am I?”, holding the space in which the answer to that question ‘floats’ through me, it’s taking the step back and let the work reveal answers I am this now, I am that, now I am this etc. It is an ongoing process. The answer is not a stable thing. I live and paint ‘inside’ of a question, how we live our daily lives every single day, a question that doesn’t have any single resolution, a question I am in active dialogue with in my life and in my relationships to other people. And so, I’ll probably die painting. What is my belief about life? What makes a life, what makes a life worthwhile? And who decides that? Life should not be a pool of misery, we work to pay our taxes and then die. I see it more as a quest for joy and artistry (at life). I also believe that the space where my self is formed is where the hope lies. I think my art is about hope, and wonderment and joy, curiosity also, about life, my own and that of others, about our vulnerabilities, the innocence, the courage, about how we find/create meaning. Everybody/Every Body counts and Every Day matters/Everyday matters. Puns all intended. I’m feeling connected in my painting. I paint what I feel, the story I tell myself about what happened, what I’ve seen, what I’ve experienced. As I paint, I figure out what (my idea of) the world is about underneath the chaos, the noise. I figure out what I’m about, what my art is about, what I value-A Still Life-which is infinitely more interesting than one would think if you look more closely. I am working now on a series of still life's, I titled ‘A Still Life.’ To me, attention to nature, to small things, mundane things can bring me great joy. In portraying trees or these humble objects, everyday matters that will remain after I’m gone, that are imbued with memories of belonging, I feel great joy and authentic, simple, pure happiness I suppose, vs the small self above, the ego self that may be driven by struggle and suffering. What is my purpose? Is that a Western question? I’m inclined not to look for purpose externally, something I have to find. Like for instance to protest violence, to make political art, to address injustice. I have done bodies of work on women’s issues, I still feel quite powerless over injustices that occur. Not so much explicit activism anymore, now I’m older. But rather as intrinsic to who I am as a person. I believe those interests will show through even if I don’t address them explicitly. Picasso-Guernica-said it well: “An artist is constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, delightful things that happen in the world.” I believe in “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower,” as in Dylan Thomas’ poem. I am no different than nature, rather I am a part of nature. A view so under stress by patriarchal capitalism, we are separate from/have to control nature etc. I am more like the bee that transfers pollen from one flower to another and keeps our environment going, and doesn’t just collect its own resources for living its bee-life. By its nature, it’s naturally serving a massive ecological purpose, probably totally unaware of that, but who knows. Nature works in cycles that way, in flow, it’s gift economy principles, not capitalist market principles. Artists make work and people receive it as we share it with the world, whether the viewers buy a work or not. Brandi Stanley makes a great conclusion from that: if I tap into what makes me feel alive-painting-then by nature, even if I’m not aware of the collective implication of what I’m doing, and may not see it in my lifetime, I may serve a deep purpose in community through my work. To finish, let me quote David Bowie, he formulates it so much better: “The reason that you initially started working was that there was something inside yourself that you felt that if you could manifest it in some way, that you could understand more about yourself and how you co-exist with the rest of society.” There it is, an artist statement. One paragraph. *Here’s Dylan Thomas’ poem: The force that through the green fuse drives the flower Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees Is my destroyer. And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose My youth is bent by the same wintry fever. The force that drives the water through the rocks Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams Turns mine to wax. And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks. The hand that whirls the water in the pool Stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind Hauls my shroud sail. And I am dumb to tell the hanging man How of my clay is made the hangman's lime. The lips of time leech to the fountain head; Love drips and gathers, but the fallen blood Shall calm her sores. And I am dumb to tell a weather's wind How time has ticked a heaven round the stars. And I am dumb to tell the lover's tomb How at my sheet goes the same crooked worm. Another one of my paintings for the book cover design series? This is from 'The Dying of the Light' series, which was inspired by a Hannah Arendt quote: “That even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination might well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and their works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given to them....” (from Men in Dark Times).

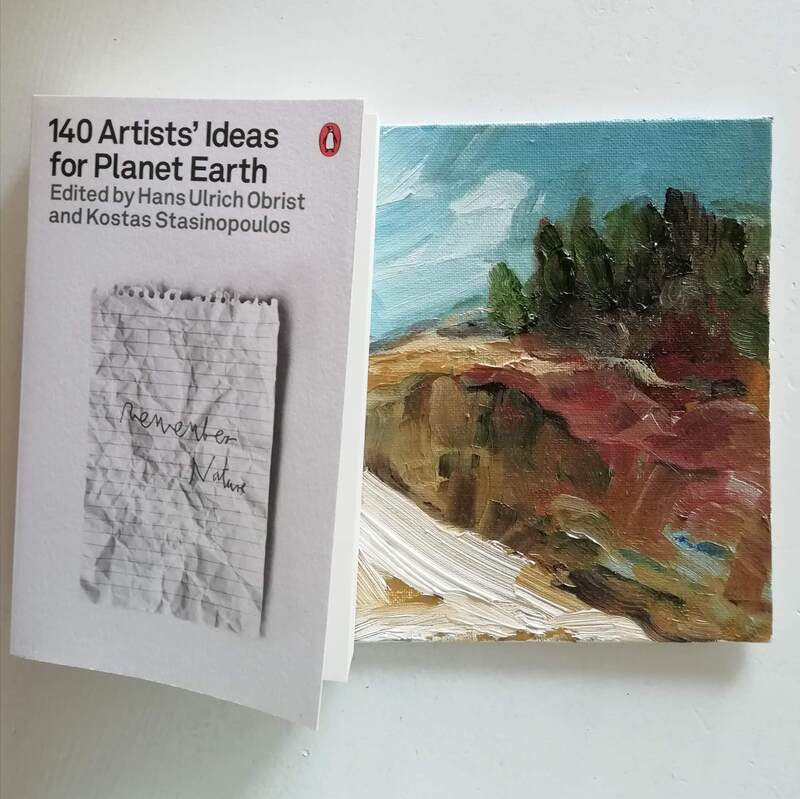

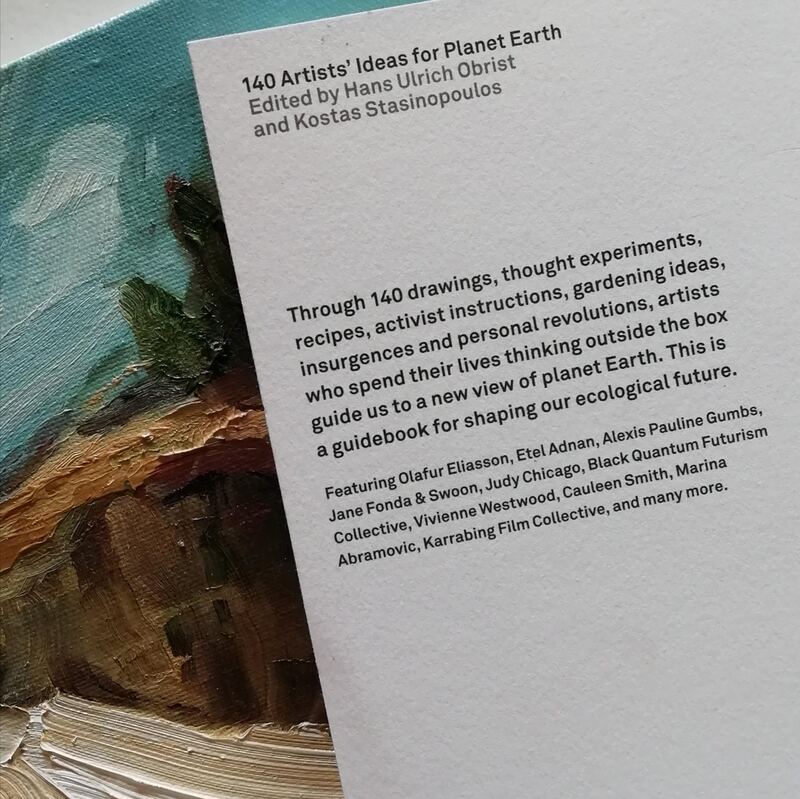

Yesterday I got Rebecca Solnit's 2016 book "Hope in the Dark," and thought of my painting. That's how my brain works. Does yours too or is that just me? In her book, she makes a radical case for hope as a commitment to act in a world whose future remains uncertain and unknowable. Solnit argues that radicals have a long, neglected history of transformative victories, that the positive consequences of our acts are not always immediately seen, directly knowable, or even measurable, and that pessimism and despair rest on an unwarranted confidence about what is going to happen next. I've been wondering about this issue, art and society, and whether art can bring hope, as a motor for societal channeling of hope into action? Solnit writes: "It is important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and destruction. The hope I am interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It is also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, though it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse one. You could call it an account of complexities and uncertainties, with openings. 'Critical thinking without hope is cynicism, but hope without critical thinking is naivety,' the Bulgarian writer Maria Popova recently remarked." Inspiring. More 'book cover visons' are in my earlier blog post . Yesterday I got '140 Artists' Ideas for Planet Earth,' at the bookstore. On my way home, I could see how the drought and heat affected the nature in our own City Park. The ducks that are usually actively toddling towards by-passers now swim in a green mucky pond. The note on the cover of the book says 'Remember Nature.' I made me think of this small mini painting 'Dry Land,' as a record so we can remember nature.

These days it seems like I'm all over the place, a mind buzzing with ideas, from still life to landscape to figurative. But there you go, 'it's all in me.' Paraphrasing Kiki Smith, 'Some people think or expect that you should make the same kinds of art forever because it creates a convenient narrative-or a coherent IG feed- ... I want my work to embody my inherent divergent interests.' 'Dry Land' is oil on canvas-board, 18 by 24 cm. During Summer Holidays, after feeling frustration with the way the world is spiralling off, I decided to start a new series titled 'A Still Life.' A play of words, since the paintings will be still lifes and they will reflect my personal still life. The idea sort of occurred to me after reading Sarah Stillman's novel 'Still Life,' the reason why I love doing still life paintings. She has some awesome writing on art braided into the story, what art does, what it means. I loved these lines in it. Like this one: "Art versus humanity is not the question, Ulysses. One doesn’t exist without the other. Art is the antidote. Is that enough to make it important? Well, yes, I think it is.” So, I'm returning to my painter self, anchoring my 'still life' in a world that seems to spin more out of control as we go. It feels almost subversive to spend hours quietly observing and rendering an object. I added Deborah Boe's poem as statement, as I often find it difficult to write about what I'm doing; I mean, who said 'if I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint'? All that emphasis on wording for artist painters ... I wonder? Maybe I'm not that kind of artist? Too many words can kill a piece. Why not be still and behold? I'm returning to read poems for that reason, their 'language' can make entering into paintings easier. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed