|

In Belgium, we went back in lockdown on November 2nd. This time I decided to make a visual diary, documenting my mood, the news, happenings in and around the house. 'Every day I write the book,' to quote Elvis Costello--every day I make a page, a painterly print, a drawing, a collage, a pastel painting with whatever I have at hand. So far I have 15 pages, I'm still working on today's. The progress is documented in a daily reel on instagram, feel free to follow my book making there. When the lockdown will be over and my book is finished I will release it, hopefully I can sell it. It's my intention to donate the proceeds to a local organisation that fights poverty helping families that are all the more impacted by this crisis. It's a plan.

Last week I attended an online webinar, organised by fiveleavesbooks and moderated by Jenny Swann. Griselda Pollock talked about 'Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology,' in which she and her co-author Rozsika Parker question whether feminist critique of Art History effected any change in the way artistwomen's works are viewed, written about in the academic sphere and distributed into the world in art publications, exhibits etc. Her answers include words like 'appaling, pathetic' about the economics of publication that exclude artists women from being seen in books, catalogs and museums. Feminist art history doesn't share an equal place in the curriculum, because of the stereotypes associated with feminist art historians/artists/writers/critics. The circuit interlacing financial value, symbolic value and public cultural understanding of why it is important for the diversity of our world to be seen in our art world isn't fully cracked yet. (An impressive numerical study of the undervaluing of artistwomen has been done by Helen Gørrill in her 2020 book 'Women can't paint, Gender, the Glass Ceiling and Values in Contemporary Art.') This eschew situation deforms our imagination generation after generation and disinforms the public. Paraphrasing Griselda Pollock: "think of those little children who go to the museums with schools and do not see themselves there, think of those young women who don't see themselves 'represented,' who don't have the experience oh look this is someone like me hanging in a gallery and the painter as well, I could do that."

The webinar took place at about the time Kamala Harris made her VP acceptance speech in a white suit, honouring the suffrage movement. Her message to young girls: “While I may be the first woman in this office, I won’t be the last. Because every little girl watching tonight sees that this is a country of possibilities. And to the children of our country, regardless of your gender, our country has sent you a clear message: Dream with ambition, lead with conviction, and see yourself in a way that others might not see you, simply because they’ve never seen it before. And we will applaud you every step of the way,”

This is not just an art world issue. All layers of public life matter and play a role in this social movement. A publication by a Belgian author Karen Celis 'Feminist Democratic Representation,' makes the argument for an intersectional update of women's group representation in electoral politics, incentivising elected political representatives to know more and care more about women, move beyond tokenism, to talk with them and not about them.

Vigilance, perseverance and keeping faith ('spreading it' as Biden says), insisting on inclusion, calling out misrepresentation is what will bring about change in how women shape their lives, their opportunities and help us all move towards a truly egalitarian society. All of us deserve to be seen, represented and taken into account. There's still lots of work to be done. This is the diptych titled 'Empty Chair,' a work I made after I was quarantined for radioactive iodine treatment to nuke remnants of my thyroid cancer now 15 years ago. I wanted to portray my bed and the empty chair. Nobody could come into that room with me, not even nurses, let alone touch me. Yesterday caregivers posted a picture of a hospital bed for a Corona patient surrounded with gear and technology on social media to alert people of the gravity of the Belgian situation and their exhaustion. On Sunday, like every first Sunday of the month in some cities around the country, there were shopping events and people went shopping en masse. Shops were offering discounts because of the lockdown going in the day after. The media named it a 'spread event'. I'm making a Lockdown Book this time around, a diary of sorts with Empty Chair on page 1. I'll add a work expressing my mood each day. Today on page 2, I added a painterly print. Let's crush the curve.

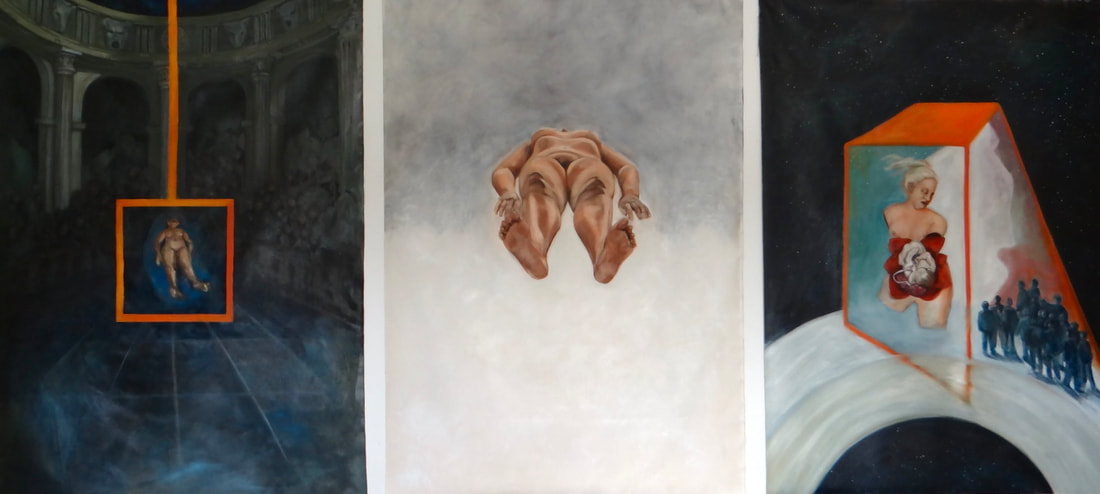

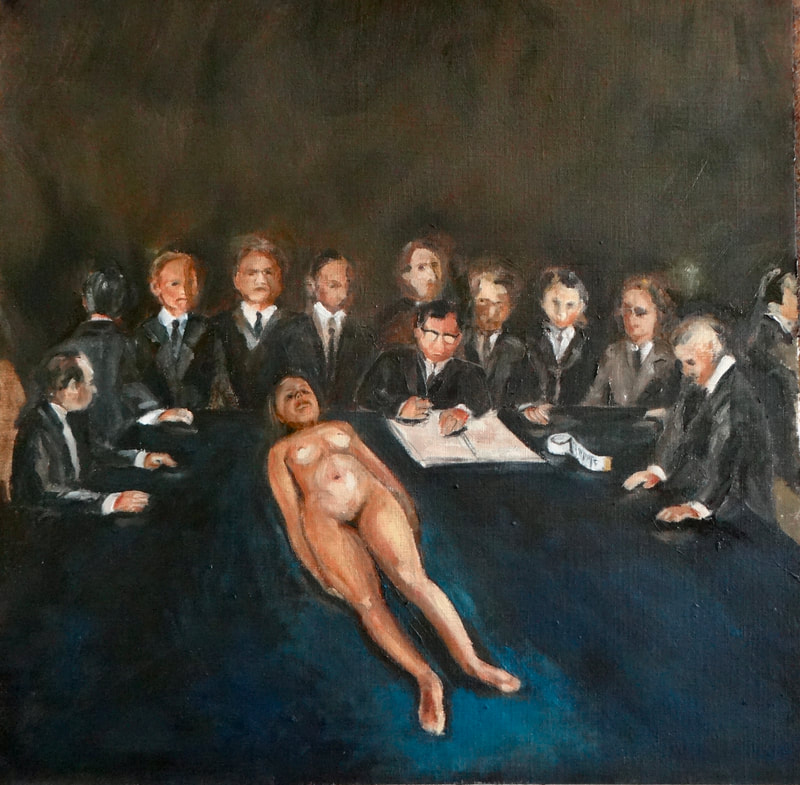

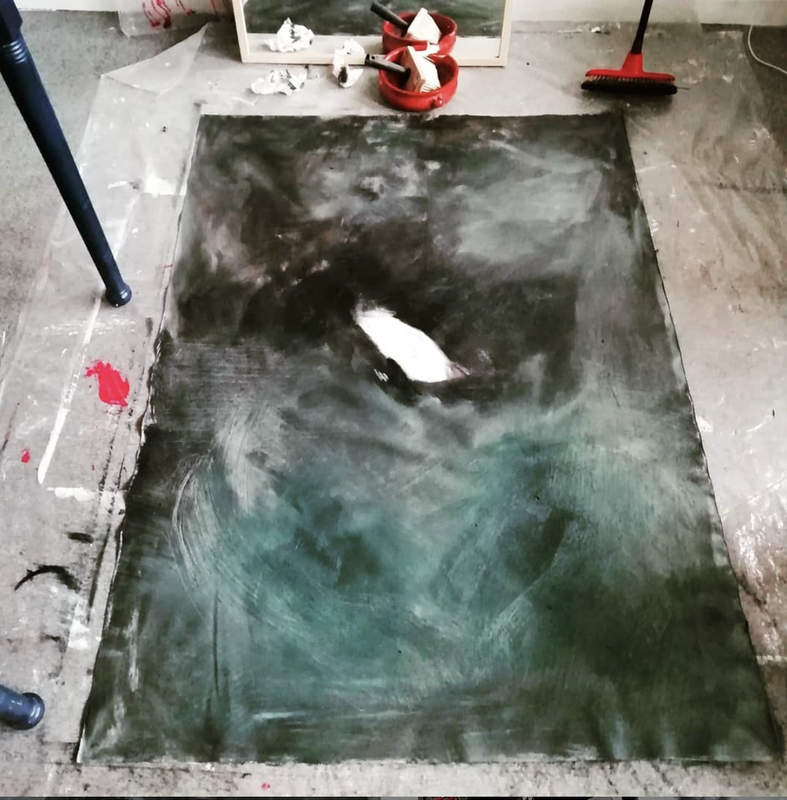

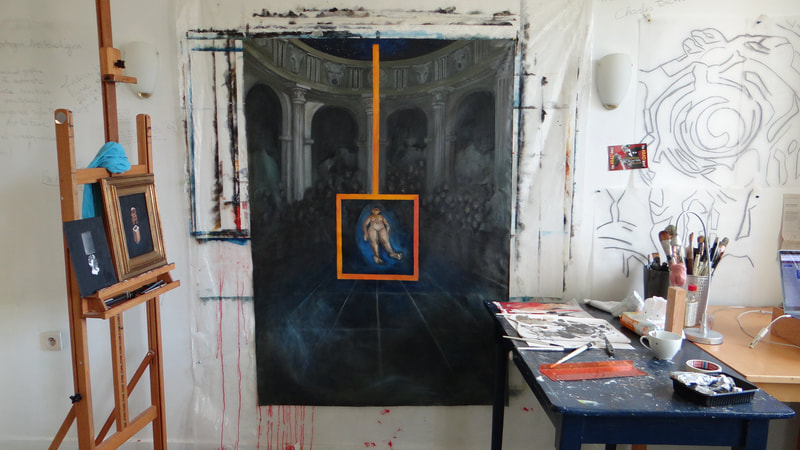

In 2005 I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Six months later with breast cancer. Both breasts were affected, I had two mastectomies. One in February 2006, one in May the same year, this one combined with a double reconstruction. In 2008 I started a visual diary on blogger about my cancer trajectories, titled painting2cancers. Going through the process I created a series of 'modified' paintings most of them based on existing artworks by male artists who painted women as subject. One of the paintings I modified was 'The Indian Dance,' a painting by Kees van Dongen. For an assignment I had copied van Dongen's work in art school years earlier. In 2009 I painterly amputated her left breast, wanting to convey that losing a breast didn't mean losing my vitality, or my womanhood as I internally experienced it. This month, I got the painting out of storage to restore damage and clean off dust and dirt. I recognised its energy but not the image. So I decided to do a painterly update and reconstruct her breast. It's a bit of a dilemma as it served as a visual record of a certain time in my life and of what happened to my body and it also served as an image to relate to for other women going through breast cancer. Emotionally though, it still feels like a self portrait to me and I want to let it progress with me as my life and my body changed. That's not to say that I will blur the scars, but even those are not that visible anymore on the outside, however much they define who I have become. It's on the easel now and I already 'see' how I'm fleshing out the figure more, the way I myself have fleshed out more into a mature woman's form with curves and more flesh in arms and legs. It's as if in 2009 I painted a young woman, too slender here and there ... And it's probably no coincidence that in The Anatomy Lesson, I again reflect on the way women's bodies are approached in art and science, by artists and researchers and doctors, men and women. I don't know about you, but I even see a visual formal resemblance in one of the paintings I made for that body of work, if only for the colour palette and its compacted energy. Last week I finally finished the first panel of The Anatomy Lesson Triptych. The Anatomy Lesson is a feminist art project, sourced from the 16th century anatomist Andreas Vesalius illustrated textbook 'De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem' and in it I am reflecting on the way women's bodies were/are approached in art and science, specifically addressing the male-centric bias therein. I started working on the first painting in December last year and am ready to call it done. The work is based on a painting I made for the #OBJECT! series. That series portrays real women and girls as they are experiencing everyday sexism, inequality, gender based violence. The piece I'm talking about refers to the 2017 Trump care bill as it was being written in the Senate by 13 men, not one woman. The bill would deny women access to the full range of reproductive health care options. Protests noted that being woman was viewed in that bill as a pre-existing condition and that the bill inferred a return to a kind of regressive gender politics in which men make the decisions about what happens to women’s bodies. A recent newspaper article discusses what the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsberg might entail for Roe versus Wade, the historic 1973 judgment that legalised abortion in the US, if Trump manages to get a third Supreme Court judge, resulting in a conservative six-to-three majority. Coincidentally, or not, in my country Belgium, the amended abortion legislation, initiated in 2016 (!), relaxing the legal period given to pregnant women before proceeding to abortion will be sent to the House Justice Committee. This as a condition for the participation of the Flemish Christian Democrats in the federal government that was being set up earlier this month. The party fervently opposes the revision. The legislation is thereby put on hold, to ensure that parliament cannot vote on and ratify it just yet. I guess 'the personal is very much political' in terms of women's bodies. The composition of the subject matter of this first panel leans on the cover illustration of the 16th century textbook by Andreas Vesalius 'De Humani Corporis Fabrica,' in which he teaches anatomical structure of men and women. The illustration depicts Vesalius demonstrating the dissection of a woman's body, in an aula, attended by students and dignitaries of the city Padua, church and university. In the syllabus, Vesalius keeps referring back and forth between illustration and text, a first in anatomy, with which the theory became clearer and many ambiguities about the human body were cleared up. Vesalius spent time at my Alma Mater, the KULeuven. I've always been intrigued by anatomy and the anatomical theatre of the university, though not from his time, imagining the anatomical studies of bodies that went on there. The story goes that the woman whose body Vesalius dissected was a prostitute who had been condemned to death for murdering a boy she wanted to use the heart and small toe of to which, she believed, magical powers were attributed. She had tried to escape hanging by faking pregnancy, but a midwife had exposed her. On the original illustration, the rope marks are still visible. What a story! This painting has been a trip. I learned a lot from working on it on and off. For starters I stressed the canvas with some unusual household tools as you can see in the progress video below. Then, only a couple of weeks ago, well into the project, I decided to get into the background and audience of this panel more. I put it back up on the wall, to do the auditorium architecture details I, thus far, was too 'resistant' to attend to, too fidgety I felt. Yet, I also remember feeling impatient first time around, which makes me unthorough, sloppy, too hasty in painting. Considering each fragment a partial painting on its own is a trick to help me focus my attention and patience for the details with respect to perspective, composition, foreground/background. The only thing left to do now, before releasing it, is straightening the painting's top edge and add eyelets to hang it on the wall, as it is, a bit like Flemish tapestry -I am after all, Flemish. Or in a box behind glass, but always unstretched. Here's the Process Video: Last week I attended a webinar hosted by the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, CT. Carolyn Wakeman, historian, gave an interesting talk titled 'Reckoning with History: Reframing the Impressionist Landscape.' She discusses how the way in which we understand the past shapes how we view the scenic places celebrated by Lyme Colony artists after 1900. With new research insights she sheds fresh light on the lived history evoked in the painted settings. The untold stories of Native Americans, African Americans as slaves brought to Old Lyme and European immigrants suggest alternative ways of seeing and framing the Impressionist landscape.

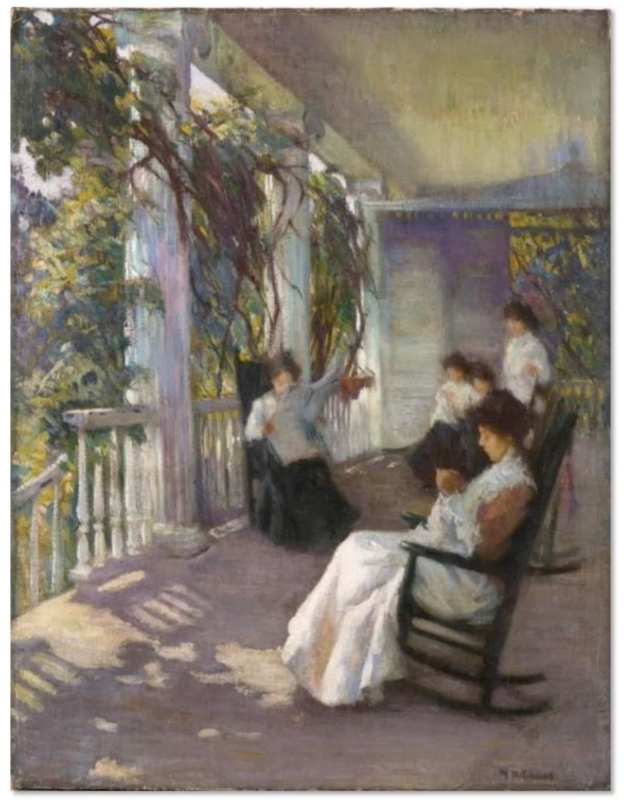

The reason I attended was that I had the opportunity to visit the Museum a couple of times while doing artist residencies in NY in 2014, 2018 and 2019. The Museum is set around the home of Florence Griswold functioning as a board house since the late 1890s for artists of the Old Lyme Art Colony, and a centre of American Impressionism. I fell in love with that house the first time I set foot on the grounds. Parenthesis: My last visit was a disappointment because the house had been taken over by an artist in residence, Jennifer Angus, known as the Bug Lady, who filled the rooms with bugs in different settings and arrangements. Let's not discuss that further. I love the house as it is kept for the visitors to see how the artists in the colony lived and worked there. Their paintings decorate the walls, but the artists also painted on the door panels of their rooms. It inspired me to paint a cow on my studio door at home, after George Glenn Newell. What else? I got the book, I got the magnets, I follow the Museum on IG, I participated in a show of theirs ... Enough said. The place is lovely and it feels as if suspended in time ... Almost at the end of the webinar, Carolyn Wakeman discusses a 1910 painting by Mary Bradish Titcomb, 'Morning at Boxwood'. In it, Titcomb portrays women in seclusion sitting on the veranda doing needle work and reading, one woman is reading the paper, connecting with events in the world around her. The artist thus seems to anticipate the change ahead for women, challenging traditional gender roles. And then, Wakeman says 'most artist wives AND Florence Griswold opposed women suffrage' and were members of the local Anti Suffrage Movement! In the after-discussion of the webinar, curator Amy Curtz Lansing coined the thought that though they might have opposed the vote for women, these women were not entirely against a more visible role for women in the public sphere; preferring women's influence therein to be exercised through culture rather than government or politics. Wakeman goes on to mention how Florence thought of her, mainly male, visiting artists as 'her (mischievous) boys,' .... And there it was, the damage done, my image of Florence as a progressive female force for artists shuttered. I may never see the house in the same light again. It all probably says more about my naive, anachronistic way of experiencing the site than anything else, being caught in a beautiful illusion. Or maybe it's just an expression of a deep-felt desire of mine that I might myself some day be matron, or member, of an artist colony or community, known for the equal representation of men, women and LGBTQ+ artists. Here's the painting discussed in the webinar and my studio door panel painting: I've completed the pages of The Missing Triangle, the book art part of The Anatomy Lesson Project. In my book I'm 'restoring' the illustration in a 16th century textbook on anatomy from which the owner cut away a neat triangle where the vagina was drawn, because such imagery was considered taboo in his (!) days. For my book I used a sketchbook and stamped each page with a clay stamp I carved in the shape of a vagina. I used three stylised designs. Their shape reminds me of Nancy Spero's 1990 imagery on The Goddess Nut, a handprinted and collage printed diptych. Lots of vagina images, fertility symbols etc, were made in prehistoric times, folklore and contemporary art. I added a few of my favorites in a slideshow below. My imagery, the stamps themselves and the printed images, connect with what in feminist art theory is referred to as 'core imagery, vaginas and vulvas,' as made by Judy Chicago, Georgia O'Keeffe, Marlene Dumas, Zoe Leonard, Mira Schor, to name a few. It's no surprise that some of these artworks resemble what I came up with, and I love discovering these synchronicities. Like for instance an abstract work by Bolivian artist Maria Luisa Pacheco, titled 'Wila,' of 1972. (I read that wila, as an Anglicized from of güila is slang for prostitute in Mexico?) Doesn't it look similar to my triangle clay stamp? I also found that the printed image of my triangular stamp looked like a world map, which prompted me to title it 'L'origine du Monde,' an interpretation of Courbet's famnous painting. I'll come back to that painting in a later document btw. What I need to do next is work on the book cover, I stamped it and will paint over that next, giving it a sort of subtle embossed effect. Then, the book art part of The Anatomy Lesson will be done. The Anatomy Lesson is a feminist body of work addressing the way women's bodies were/are approached in art and science. The project comprises painting, sculpture, bookmaking and monotype printing. More on my site viewing room dedicated to the project. While doing research on the history of anatomy illustration, you unavoidably find the 18th century wax anatomy models. These wax women models, some made by women artists (!) like Anna Morandi, were used as a means to instruct. In our times, they also confuse the viewers as the women models are almost a representation of the ideal female beauty, often referred to as 'the Anatomical Venus,' 'Little Venus,' or 'Sleeping Beauty.' They tend to be in fine attire, wearing pearls and positioned in seductive, bordering on the erotic ecstatic, poses. According to Joanna Ebenstein who conducted research into them, the models were a perfect embodiment of the Enlightenment values of the time, in which human anatomy was understood as a reflection of the world and the pinnacle of divine knowledge: to know the human body was to know the mind of God. The 1543 textbook 'De Humani Corporis Fabrica' of Andreas Vesalius, on which my art project is based, was illustrated with woodcuts thought to be by Titian’s studio in Venice. That overlap of art and science disciplines was the background for the anatomical Venus sculptures. The division between art and science, and between religion and medicine we have now, didn’t exist at that time. In her analysis, Ebenstein compares the models' appearance and expressions to sculptor Bernini’s, 'The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1652)' to argue that the ecstatic was understood at that time not merely as a profane, sensual experience, but also as an expression of the sacred, as a mystical experience. For me the question remains, why images of religious ecstasy were almost sensual, erotic in nature, for women? It seems like an interesting research topic to see how religious ecstasy is 'portrayed' in men. And how would such a differential study be titled? I found some images on Fine Art America, see what you think? I also discovered feminist art that alludes to these wax models as I was studying Katy Deepwell's online course on Feminism and Contemporary Art. There's Zoe Leonard's 1990 photo `Wax Anatomical Model (Shot Crooked from Above), of which she said (as quoted in Laura Cottingham) "I first saw a picture of the anatomical wax model of a woman with pearls in a guidebook on Vienna. She struck a chord in me. I couldn’t stop thinking about her. She seemed to contain all I wanted to say at that moment, about feeling gutted, displayed. Caught as an object of desire and horror at the same time. She also seemed relevant to me in terms of medical history, a gaping example of sexism in medicine. The perversity of those pearls, that long blond hair." In these feminist artworks, the models, the figures become a tableau or women artists use them in environments to explore rituals, stereotypes and to question women's cultural objectification. There's also Suzanne Lacy's 1977 photo series 'Anatomy Lessons' (!), using imagery of organs and peeling skin to suggest psychological states such as the humiliation of exposure or the experience of confinement, works that explore what constitutes identity, gender, and the body. I guess my body (!) of work 'The Anatomy Lesson,' ties in well with this category of woman artists' practices. I'm resuming work on the first panel of The Anatomy Lesson Triptych, the first painting of The Anatomy Lesson body of work I started in December last year. Progressing on the other pieces, paintings, sculpture, prints and book art, I decided to go in again and add more detail to that first work. The painting refers to the cover illustration of the 1543 syllabus 'De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem,' on which anatomist Andreas Vesalius is portrayed during an anatomical demonstration. The Anatomy Lesson is a feminist body of work addressing the way women's bodies were/are approached in art and science.

The works are sort of a spin-off from an #OBJECT! painting I made in 2017. That series consists of poster-like paintings of women and girls sourced from images and stories on the web and in written media. The works 'portray' real women and girls as they are experiencing everyday sexism, inequality, gender based violence. The series paintings are in one of the galleries on my site here. The particular piece I'm talking about was made as the Trump care bill was being written in the Senate by 13 men, not one woman. If you look closely, you might recognise Bannon, Kushner and Stephen Miller in the painting. The bill would deny women access to the full range of reproductive health care options fundamental to women’s economic security. Protests noted that being woman was viewed in that bill as a pre-existing condition and that the bill inferred a return to a kind of regressive gender politics in which men make the decisions about what happens to women’s bodies. In the newspaper today an article discusses what the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsberg might entail for Roe versus Wade, the historic 1973 judgment that legalised abortion in the US, if Trump manages to get a third Supreme Court judge, resulting in a conservative six-to-three majority. Coincidentally, or not, in my country Belgium, the amended abortion legislation, initiated in 2016 (!), relaxing the legal period given to pregnant women before proceeding to abortion from 12 to 18 weeks, will be sent to the House Justice Committee. This as a condition for the participation of the Flemish Christian Democrats in the next federal government, after the May 2019 (!) elections. The party fervently opposes the revision. The legislation is thereby put on hold, to ensure that parliament cannot vote on and ratify it just yet. I guess 'the personal is very much political' in terms of women's bodies. In the body of work titled The Anatomy Lesson, I'm creating a series of paintings inspired by sixteenth-century Andreas Vesalius’ anatomy textbook ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica.’ I'm addressing the incomplete way women’s bodies historically were approached in science, due to traditional beliefs, preconceptions or stereotyping, often serving to legitimise women’s ‘inferior’ social status, leaving women vulnerable in health issues. I was working with this sixteenth-century textbook during the Belgian lockdown, following daily updates on the corona virus spreading around the world, realising this body of work, paintings of human bodies, is actually timely and relevant, as it points to our corporeal vulnerability. The research that is being set up into why women’s immune system seems to be more effective in fighting the virus than men’s shows the importance of gendered research and thankfully we’ve come a long way since Vesalius. Although, Alyson McGregor, MD (!)' 2020 book, Sex Matters argues that all models of medical research and practice are based on male-centric models that ignore the unique biological and emotional differences between men and women, an omission that can endanger women's lives. Still. The Anatomy Lesson comprises paintings, sculpture and book art. In the works I'm visually reflecting on the way women’s bodies were depicted and studied in the sixteenth century textbook of Andreas Vesalius, an anatomist who taught at my Alma Mater, the KULeuven. During my research I found that in a sixteenth century anatomy book instead of a vagina, only a missing triangle remained from the illustration of a semi dissected woman’s torso. In Vesalius’ time, sixteenth-century Christian society, female genitalia were considered taboo. Female flesh was associated with sin and naked women depicted as satan’s servants. Before that, women’s genitalia were thought of as lesser versions of the male organs, turned inside out. Based on this, I started to make an artist book, The Missing Triangle. In it, I'm searching to restore this illustration from Vesalius' textbook, by using stamps I carved from clay on each page. In its entirety, want to create a body of work that visually brings all those aspects together, addressing that some biases in research methods stretch out over time and compromise the research environment even today, as science journalist Angela Saini describes in her book ‘Inferior.’ This is not only bad for gender equality, or the place of women in science, it’s bad for science and for the understanding of human life itself. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed